Reclaiming Identity: Nigeria’s Middle Belt’s Enduring Struggle Against Mislabeling and Marginalization

Nigeria

Features

For generations, millions of Nigerians from the Middle Belt—home to diverse ethnic groups such as the Tiv, Idoma, and Jukun—have wrestled with an imposed identity as “Northerners.” This mislabeling is not just a matter of semantics but a deep historical and political challenge that has obscured their rich heritage, watered down their political influence, and undermined their cultural pride. As one scholar describes, the Middle Belt’s identity crisis represents a profound human story of resilience and the universal aspiration to be recognized for who they truly are.

This identity crisis finds its roots in British colonial policy, which worked closely with Northern elites to subsume the Middle Belt under the dominant Hausa-Fulani emirate system. According to historian Moses Ochonu, the British modeled indirect rule on the Sokoto Caliphate’s emirate structures and attempted to expand this model even into regions like the Middle Belt, where local groups resisted caliphate control. This colonial design ignored the varied histories and systems of governance in the Middle Belt, effectively erasing indigenous identities and creating long-lasting divisions.

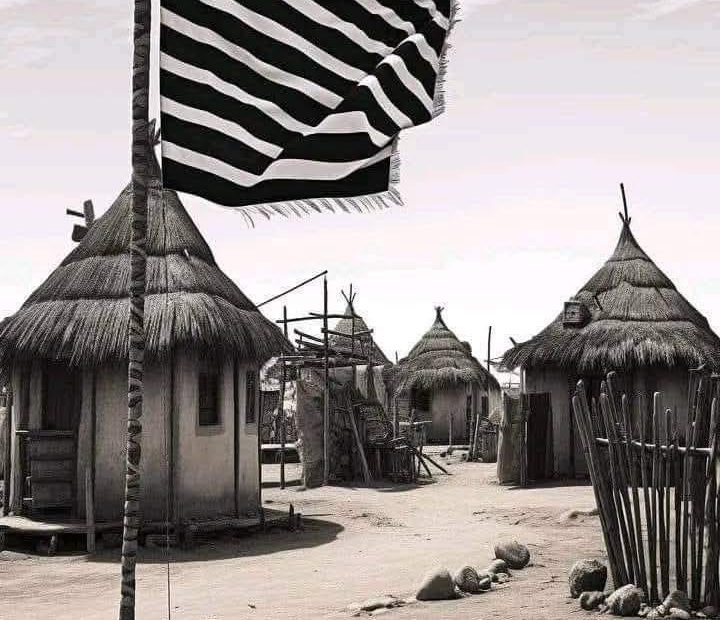

The Tiv people, the largest ethnic group in the Middle Belt, vividly embody the region’s distinct heritage. They migrated from areas around modern-day Cameroon into Nigeria’s fertile Benue Valley early in the 17th century, though oral histories trace their roots even further back in time. Pre-colonial Tiv society was organized without a centralized king. Power resided with clan elders, with social harmony enforced through kinship ties and consensus. Archaeological studies conducted at Benue State University document how the Tiv established fortified hillside settlements to resist slave raiders and protect their communities, a testament to their long-standing resilience.

The Middle Belt’s historic role as a refuge stands out during two tumultuous eras: the transatlantic slave trade and the Fulani Jihad. The region sheltered numerous displaced peoples fleeing slavery’s brutality between the 1500s and 1800s. Moreover, while the Fulani Jihadists conquered much of Nigeria’s far North, the Middle Belt mounted fierce resistance, halting their advance. Scholars explain that unlike other northern regions absorbed into the Sokoto Caliphate, the Middle Belt retained its independence and cultural distinctiveness throughout this period.

Colonial rule further soured the Middle Belt’s fortunes. When Nigeria was amalgamated in 1914, the British sought to impose centralized control via indirect rule. But rather than recognizing the Middle Belt’s unique identities, the colonialists subordinated its peoples to emirate authorities based in the North, essentially disenfranchising them. The British cultivated divisions among the region’s diverse tribes and installed Muslim emirs as political agents, exacerbating ethnic tensions. This divide-and-rule strategy, documented in academic studies, fueled resistance movements and calls for recognition among Middle Belt leaders, including prominent Tiv politician J.S. Tarka.

At independence in 1960, these colonial legacies persisted. The Middle Belt was fragmented into multiple states, including Gongola (later Adamawa and Taraba), Benue, and Plateau, deliberately weakening the region’s political cohesion. Political scientists describe this state-balkanization as a method to dilute the Middle Belt’s influence and maintain Northern dominance in shaping national policies. Despite this, the region’s population—over 50 million people—remains Nigeria’s second largest, and it produces about 70% of the nation’s staple foods, underscoring its critical role in the country’s economy.

Beyond politics, the struggle for Middle Belt identity arises in deeply personal ways. The daily lives of millions—farmers, traders, artisans—are woven into the land and its history. Anthropology research reveals stories of Tiv families who recount their ancestors’ defiant stand against slavery and jihad, as well as their community’s rich cultural celebrations which affirm kinship and independence. For many, being categorized simply as “Northerners” diminishes these lived experiences and the pride that comes from knowing one’s deep roots.

The Middle Belt’s fight to reclaim its name and identity is thus not mere political rhetoric; it is a quest for justice, dignity, and meaning. Scholars studying regional memory politics argue that recognizing the Middle Belt’s unique history fosters inclusion and strengthens national unity by honoring all peoples’ contributions to Nigeria’s nationhood.

As Nigeria moves forward, embracing the Middle Belt’s identity is critical for lasting peace and equity. The region’s tribes—Tiv, Idoma, Jukun, and many others—deserve recognition that reflects their ancient heritage, their sacrifices in resisting domination, and their vital role as the nation’s “food basket” and demographic center. Their stories, documented in diverse historical and ethnographic sources, demand acknowledgment and respect.

Ultimately, the Middle Belt people speak not just as a region but as a human story of perseverance and the right to be known on their own terms. The time has come for Nigeria to listen and recognize them for who they truly are: Central Nigerians, proud and integral to the nation’s collective future.